The Squat

The deep squat (aka full squat, aka ass to grass/ATG squat) is one of the most debated, talked about exercises/assessment we have in human movement. Some talk about the deep squat as if it’s the cure to cancer, some talk about it like it’s going to cause the apocalypse. I have found that I always get mixed information and many take either a full medical approach, a full evolutionary approach, or a full performance approach.

My goal here is to provide a blend of these approaches. As a PT that loves S&C and evolutionary medicine, I hope I can give some evidence, some reasoning, and some clinical judgement on the deep squat as an exercise.

Let me again emphasize this is through the lens of the deep squat as an exercise; the squat as an assessment is a whole different story.

If you want to stop reading here, please consider the conventional wisdom of great S&C coaches:

- Squatting is not bad for you, the way yousquat is bad for you

Disclaimer

I think a big part of the discrepancy with the performance with the deep squat is that there are so many variables associated with this movement pattern. These variables include local physical impairments, movement history, exercise history, injury history, education, neuroception, structural changes, coaching, motivation, and culture.

So if you took 100 people off the street and had them deep squat, you would see a smorgasbord of different movement patterns.

This surfeit of human variables leads to a problem when trying to generalize one of the world’s most complex exercises, let alone trying to create a study.

But this abundance of variables isn’t the only problems with the studies.

3 Reasons Why Evidence isn’t the Gold Standard for the Deep Squat

- The populations vary from individuals who are young and have experience with the deep squat, to older individuals with possibly no experience with the deep squat.

- The studies don’t seem to take into consideration any of the physical impairments; someone with an ankle dorsiflexion restriction is going to squat much differently than someone with a ankle motor control problem.

- The definition of the deep squat is completely different in some papers (some have mentioned parallel femurs as a deep squat).

So you can’t expect too much from PubMed due to the inconsistent populations, lack of data on physical inputs, and a poorly defined task.

Defining the Deep Squat

I’m going to call the deep squat simply a squat below parallel with a neutral spine.

If you can’t get below parallel with a neutral spine, you can’t do a deep squat as an exercise.

Getting below parallel with spine flexion is great if it’s unloaded (SFMA, PRI), but in this article I’m focusing on the act of loading the deep squat for strength, performance, & movement enhancement.

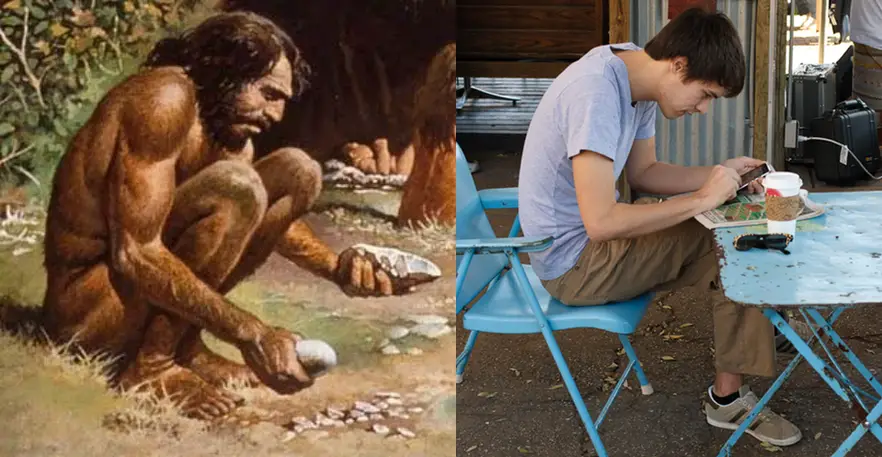

We Used to Always Squat

Tired of standing? Squat down.

Need to check something out or inspect an object? Squat down.

Hanging out, shooting the shit around a camp fire? Squat down.

This was the life for our ancestors (and for some of our current species in different cultures).

It’s Phylogenetics, the evolutionary history of our species. It’s our species’ “family tree” from the beginning of time.

The way our bodies have evolved over time has resulted in the movement pattern of the deep squat.

But it’s also Ontogenetics, the developmental history of an individual. It’s how the interaction of genetics, developmental programming, and environment affects the physical form throughout a lifespan.

I’ve mentioned in a previous post that we have culturally evolved at a rate that far surpases our physical evolution. Meaning, the world we live in is not made for our physical structures (chairs, shoes, school/work, technology, etc.).

This mismatch means that the person in front of you trying to squat should be able to squat (phylogenetics), but may not be able to because of the way they have interacted with their environment (ontogenetics).

For example, think of how a 4 year old can deep squat with no problem (phylogenetics), but the 50 year old, life-long sedentary, American desk jockey that can’t flex his hip past 90 degrees because of structural changesin his femur/acetabulum has no chance at a deep squat (ontogenetics).

But before you start analyzing your patient’s phenotype, you should first understand the benefits, risks, and drawbacks of the deep squat exercise.

A Visual Approach to Squatting

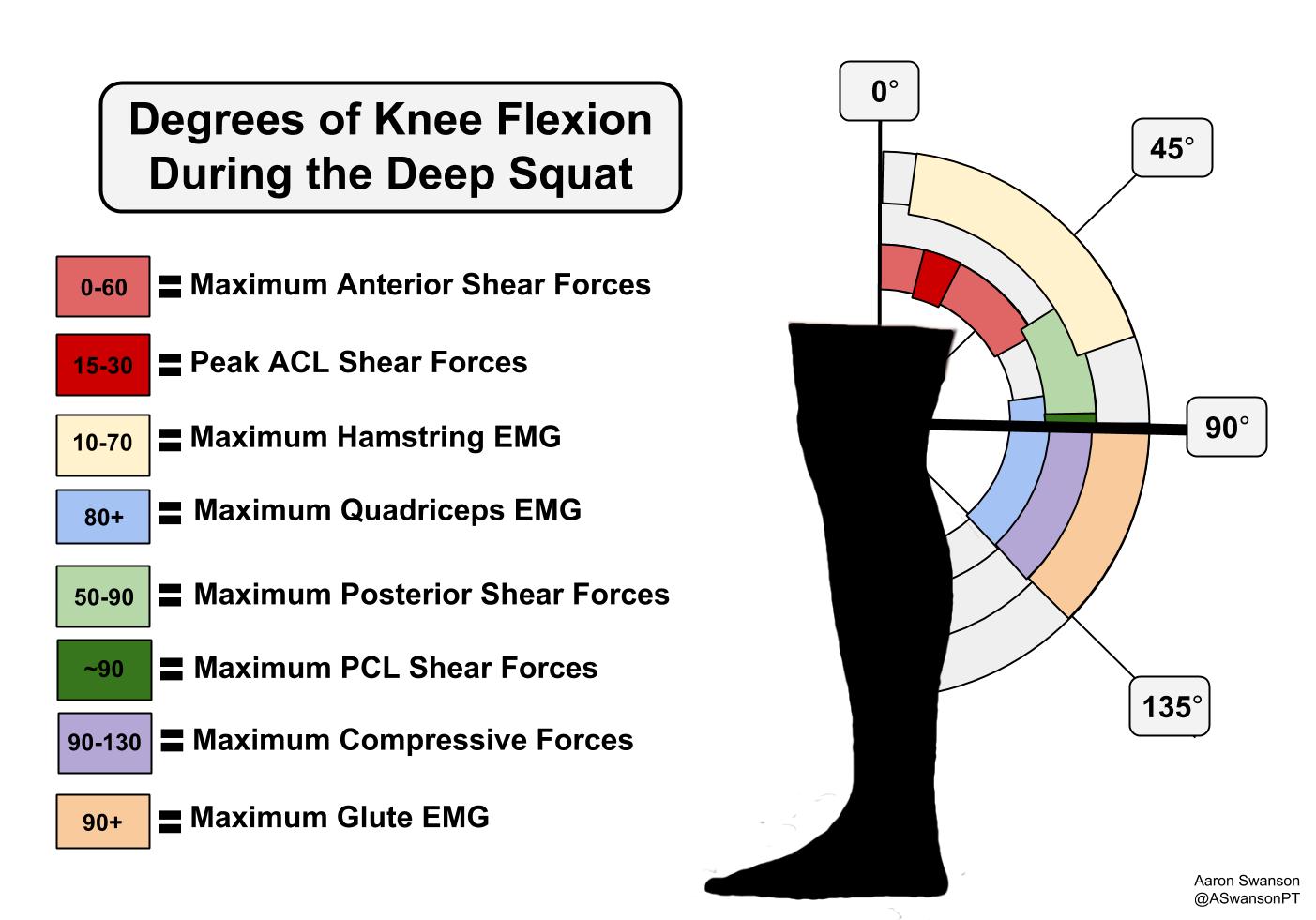

Before discussing the benefits and potential drawbacks of the deep squat, it’s best to understand exactly what is happening at the knee joint through varying degrees of knee flexion.

Here’s a diagram with the degrees of knee flexion and the associated forces/EMG activity.

This is based on several studies, listed below.

* Most studies don’t mention any activity beyond 135 degrees. So this is unknown and why there is nothing beyond 135

** It seems the force shifts from anterior to posterior between 50-60 degrees. This is why there is an overlap. Yes, I know it’s impossible to have both anterior and posterior shear forces at the same time.

Why it’s Good

It cures cancer!

But seriously, the deep squat exercise has a ton of benefits (see chart below).

In general, the deeper the squat, the greater the quad and glute activation.

Plus, the deep squat spares the knee of shear forces and prevents ligamentous strain (see figure above). Since most lower extremity injuries involve weakness and aberrant shear forces, the deep squat can provide a great exercise to help reduce injury.

From a performance perspective, the deep squat provides a great exercise for increasing strength (legs, thighs, hips, core) and improving vertical (y-axis) movement efficiency.